KNOWLEDGE AND LANGUAGE

WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN KNOWLEDGE AND CULTURE?

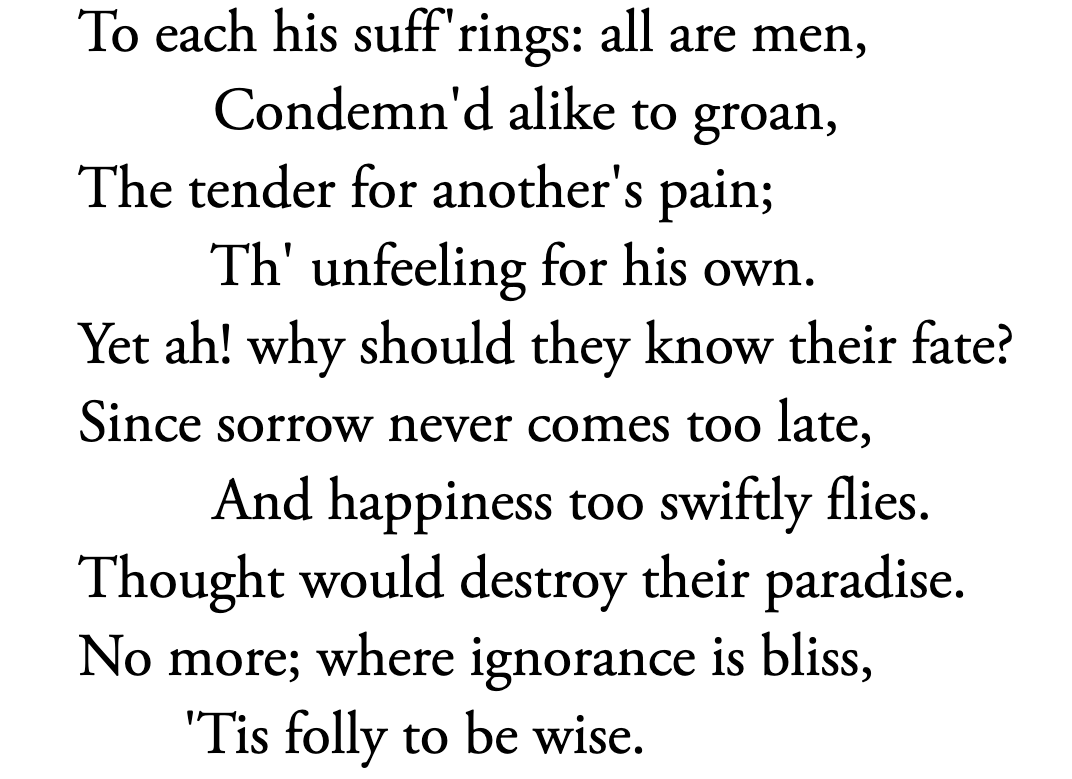

Gray, Thomas. “Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College.” 1768. Poetry

Foundation.

source

This is the last stanza of Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College, an 18th-century ode by the English poet, Thomas Gray. In this poem, Gray invented the phrase ‘Ignorance is bliss’. I’ve been introduced to this phrase many times throughout highschool; most of them to debate whether there is truth in the statement or not. Of course, there is a general understanding that ignorance isn’t a favorable state of mind, and that it’s better to be equipped with all kinds of knowledge for all kinds of situations. Because this was before I had ToK classes, I had a superficial understanding of the background and impact of this phrase. I didn’t realise that the phrase I considered to be common culture, was actually only better known within English-speaking contexts. This grand debate about an iconic phrase had a limited audience that I had completely neglected. This brings out the issue of language barriers and how they help protect certain aspects of different cultures and CoK. For example, while the essence of the phrase ‘Ignorance is bliss’ can certainly be discussed in any language, the experience will be different to an english speaker analysing a small phrase from an 18th-century ode. At the same time, while this poem has a very specific context, it has become part of a culture that has obliged it to transcend into today’s modern world. In addition, there is something particular about the distinguished phrase; it has been slightly misinterpreted. The complete phrase, ‘where ignorance is bliss, ‘Tis folly to be wise’ demonstrates that Gray presented an affirmation, but not in favor of ignorance. Instead, it declares that within a context in which ignorance is the norm, knowledge isn’t imperative. To me, this perfectly portrays how a subjective form of communication like literature, can be a cultural symbol that transcends time but at the same time, doesn’t transcend a language barrier.